several years ago i spent a few months in india doing tsunami relief work and traveling. i didn't realize i'd been bitten by the india bug until i moved back to my comfortable, yet predictable life in new york. it didn't take long for me to relocate to india full-time to try to make a life. now, after three years in mumbai, i split my time between america's east coast and india's west coast. the difference between life here and life there is that everything in india begs to be written about.

Thursday, May 26, 2005

Thank You

For nearly three weeks after I returned home from India, I awoke nightly thinking about everything I'd left behind. Even now, nearly two months out, India crosses my mind daily—luckily, not at 4 AM. Mostly, I think of the people I met, a girl named Susila, newly-orphaned Rahel, the wrinkled old fisherman; I recall their spirit and resiliency. That they now have a place in my memory is a gift, made possible by the generous support of family, friends and a few goodhearted strangers.

The money and support you provided helped the neediest and most deserving: survivors of the 2004 tsunami and Orissan orphans. The funds bought several hundred kilos of rice for an island community that had run out of food; supplied saris and lungis to several hundred women and men who had lost everything; gave 110 orphans coloring books, crayons, flashcards; and allowed me, as your representative, to act as a goodwill ambassador.

Thank you for your contribution—whether you attended the fundraiser, gave money, offered encouragement or lent emotional support. Your compassion enabled me to touch thousands, and for that I am forever grateful.

Annie, Ananda and the rest of the crew at Ara

Nabil Aidoud

Virginia Alexander

Pam Arthur

Kirk Bedell

Bryce Baradel

Jess Bolkcom

Caroline Boudreaux

Jen Branam

Mendy Brannon

Laura Brueck

Jen Bruno

Stacey Callahan

Matt Chapman

Mike Christopher

Hazel Clinton

Scot Clinton

Katy Daly

Jamie and Kevin Donner

Lauren Franzel

Vanessa Fontanez

Ali Froman

Kristen Gelder

Kate Golden

Hattie Grouber

Frank Griffiths

Gardner Harris

Audrey Hayden

Kara Hill

Alex Jaini

Lisa Jeffries

Jennifer Jones

Will Kain

Pam Kaupinen

Wes Kaupinen

Kendrick and Tracy

Kim, my dental hygienist

Megan Mann

Anna McDonald

Mimi Mayo

Jessica Meli

Lindsay Mendoza

Brooke Michael

Vanessa and Scott Myers

Narayanan P.R.

Carter Paine

Jay Patel

Jay Patel (there are two)

Kirin Patel

Caroline Puri

Dr. Kunal Puri

Dr. Richa Puri

Holly Reed

Les Rogers

Natalie Ryan

Alice Sarfati

Maziar Sassanpour

Shaolee Sen

Dr. Subroto Sircar

Alexis Tessier

Mary Ann Torrence

John Twomey

Jenny and Robbert Vorhoff

Whitney Watson

Pat Werblin

Saturday, May 07, 2005

Calcutta

“If you were a better liberal, you’d save that goat,” Pitt told me as we watched a diminutive, furry black goat receive a blessing of orange powder on his forehead in preparation for his impending sacrifice. I fiercely inhaled heavy air and wondered if I should leave. But, I couldn’t. There were two brown urchins holding onto my legs. I focused on their steaming little bodies holding tight to my legs, little tree huggers, and looked down into their laughing eyes. I tried to ignore the squalls of the goat. But, in retrospect, even if the babes hadn’t latched onto me, I wouldn’t have moved to save him. Instead, I came when Pitt motioned for me to watch from a better vantage point near him. And, steps from the chopping block, the energy building in crescendo, I winced as the goat came undone.

I felt strange about it afterwards—watching him die—so we left immediately, stepping over skinny women in wrinkled, cotton saris on the way out the temple gates. By this time, I had figured out that tickling the little leaches on my legs would make them release their grip, and forget about asking for rupees.

The heat combined with the smell of goat blood, which was all over the ground, along with the thwack of the scythe as it beheaded the goats was sensory overload. We left and went to the waterside for some air at Kalighat, a shrine-filled area with steps that lead down to the water. We were lucky there was no breeze that morning, because the river water was malodorous and filled with brown sludge and plastic trash. But, it was away from the Kali temple, where more than twenty goats had already been killed that morning, and more than twenty more would be killed before the sun reached its zenith.

From Kalighat, a word that a seafaring Brit is said to have mangled,

Calcutta, continued

If I made a diorama of Calcutta, and your eye peeked in and wandered over the temple scene, aghast, it would be all the more surprised by the scene outside of the temple, a couple of streets away, closer to the city center. Beautiful, old, decaying buildings rise up in faded brick red and mossy green, accented with thick wooden shutters, and latticed balconies. Echoing the chaos of

I wasn’t expecting the goat sacrifice, but then again, I wasn’t expecting a cosmopolitan place either. My mother loves to tell the story of her friend, a mature, single, well-traveled woman, who flew into

As culturally ignorant as it may sound, the only thing I have ever heard about Calcutta concerns its horror stories and unimaginable poverty. But, evidently,

At the start of the trip, I had decided that I would not be making the trek to

The trip from

Third class A/C was a complete revelation. We were given sheets, blankets, towels, a snack of cheese sandwich and mango juice, a nice vegetarian dinner, chai in our own thermos, and free bottled water. Every time the waiter appeared, he brought another surprise—biscuits? Ice cream? Fresh coffee? I had balked at the $38 train ticket—expensive for an

When the train pulled into the station, I galumphed off, an awkward llama with a heavy load, and was wholeheartedly greeted by

With the exception of the day of the goat sacrifice, I spent most of my time walking around and visiting some of

During my stay, I thought about Zana Briski’s Born Into Brothels, a documentary about the children of prostitutes in

_______________________________________________________

Saturday, April 09, 2005

Friday, April 01, 2005

Friday, March 25, 2005

Sunday, March 20, 2005

From Delhi to Rishikesh. Well, almost.

*N.B.: The following six articles are part of a series written about

experiences in Rishikesh. They loosely follow one another...they are

best read in descending order.

I arrived in Rishikesh, so called "Yoga Capital of the World," about a

week ago and nearly left immediately. The place didn't match the

descriptions I had heard from other travelers, who described it as a

magical place: a mini and more manageable

to be charming, a place with spiritual energy, but without the grit of

two weeks on the internet, a well-known ashram, and I was excited

about experiencing that kind of atmosphere. But, what I imagined I'd

find—a holy, unostentatious place of quietude and solace—was actually

a bit off, like taking a swig of cold creamy milk, only to find that

it's sour.

Everything looked okay, but the atmosphere was peculiar. Rishikesh

was filled with sadhus and cows, like

poor imitation, like its soul was made of wax. Admittedly, the ashram

was beautiful, with large treed courtyards, slippery tile walkways,

and over 1000 rooms. And, it was almost mystical because chanting

constantly filled the empty spaces in the air. But, while mystical,

the atmosphere was also very unusual. Around every corner were boys

wearing bright orange robes, studying to become priests, and each

courtyard was filled with wildly colorful pastel painted statues of

Hindu gods. Unfortunately, the people I encountered were absolutely

impossible to communicate with—not because of a language barrier, but

because they desired to be difficult—and this did not add to the

experience.

Perhaps I wasn't in the mood for Rishikesh or the ashram experience,

though. The trip started quite poorly in the first place. The bus

from

And, the driver decided not to stop in Rishikesh at all. I shouldn't

have been that surprised. But, it was dark, and I was tired, and not

of the disposition that took this slight lightly.

The way the bus ride transpired was completely Indian in nature: we

left two hours late; we made multiple stops to pick up people on the

side of the road; and, we never made it to our destination. Since I

was the only person on the bus going to Rishikesh, and more people

were going to the next stop, the driver made the executive decision to

just drop me off wherever he liked, which meant, for me, in the middle

of nowhere. I am not a fan of Greyhound, the not-so-sleek American

bus company, but to its credit, I doubt that a Greyhound driver would

ever drop a passenger off on the side of the road at night to fend for

herself.

Usually, I would just accept this sort of situation, but on this

particular night, I was not in the mood, and managed, in the process

of being booted off the bus with all my gear, to throw a royal fit.

After quite a bit of thrashing about and using my "angry woman" voice,

I coerced the ticket collector into giving me money for onward

transportation to Rishikesh. I also told him that he needed to find

me a taxi or rickshaw. He refused. I appealed to the rest of the

members of the bus, hoping that someone would understand me or take

pity and help. I doubt anyone really understood what I was saying,

but from my face and my livid gesturing, I think they got the idea. A

young Indian gentleman spoke up, and told the ticket collector to get

me a rickshaw. He begrudgingly did. It took fifteen minutes for a

passenger vehicle to come along, but he finally hailed a group

rickshaw and we bid each other bitter farewells.

So, after a cold rickshaw ride and a hike to the ashram, I entered my

room and fell into bed. Chanting filled my ears and continued for

hours into the night. I closed my journal entry that night with this

slightly judgmental first impression: "This place is a weird cult."

Ashram

The next day, the Ganges, which divided Rishikesh into two banks,

drank up a cool, steady rain. I walked, arms akimbo, across the

grounds of the ashram concentrating on every step to keep from

slipping on the slick tile walkways. Over email, I had enrolled in a

two week beginner's yoga course at the ashram taught by an American

woman. The course seemed to be a full-service operation including

meditation, asanas, chanting classes, and tutorials in the

Bhagavad-Gita (one of India's most holy texts). That rainy morning I

asked four different ashram people about the "Beginner's Yoga Course"

and was told three different start dates, and, from one particularly

confused fellow, that there was no course at all.

That was off-putting, but not surprising—in India there's often a

different answer to the same question depending on who you ask.

However, I was repelled by something else, as well: "obsessive

Swami-worship." Many ashrams are started and led by a guru of some

sort. And, I have been warned that some ashrams focus on the leader

more than their mission. My ashram was led by a long-bearded,

orange-clad guru whom everyone seemed to adore.

But, over breakfast the first morning, I observed several guests being

shushed. A pleasant looking Indian man told them that silence was to

be observed until 10 AM, because "the Swami is meditating!" One

couple, a newly married Asian bride and groom, both dressed in

spectacular silk clothing, sat in the front office outside the

breakfast area waiting to meet His Holiness, perhaps to have their

marriage blessed. I kept overhearing conversations about how

"impressive He is in person," and how "He doesn't say anything, but

you can just feel His power." I reflected for a moment, over my bowl

of steaming sweet wheat porridge, and then quietly tiptoed back to my

room to pack.

Rain

There's nothing like the sound of a thousand raindrops trotting on a tin roof. Today during Pranayama, the breathing portion of our yoga class, the evolution of a storm stole my focus. I neglected my lungs and abdomen and let the thunder bowl through me, its knees and elbows banging into walls, clanging about above my head, taking over the sky.

The raindrops came soon after, loud, like schoolboys spilling marbles on a sheet of glass. After a heavy onslaught, the droplets slowed. Rivulets ran down leaves looking for a nice place to land. Spheres of water tumbled down temple ramparts, happy to roll, and then leap, roll, then leap, picking up speed, flipping over once, twice, splaying liquid arms then curving into a droplet again and galloping over the next edge. It smelled as if God had ripped open a thick, yellow-veined, green leaf and the moist, fresh earthy smell took over everything.

The asphalt darkened into deep slate, and the cow paddies and afternoon detritus dog-paddled to a nearby drainage canal. These narrow, cement canals run parallel to the road on both sides, accepting the debris and dirt that's been discarded in the street.

When it pours, water speeds through the drainage-ways, and little Indian boys and girls kneel to watch, rapt with attention, as trash rushes by underneath them. For an adult, it's difficult not to be disgusted by the junk that bumbles about, bobbing from one side to the other. But, the children must imagine the floating bottles and bits of brown paper and plastic wrappers as bobbing sailboats and flashy fish. A little girl twings a piece of silver foil through a steel grate into the water passing below and smiles as it drops and floats downstream. She sighs with delight at her creation.

I inhale the rain smell, and wiggle into my mat, trying to once more focus on my breath and watch my inner nature, all the while wishing the rain would stage another hoe-down above my head.

Neerag

Even though Neerag is just a boy, I couldn't let him take advantage of me. As a result of my refusal, Neerag wasn't happy with me for the rest of the day, but after he delivered a bucket of hot water that evening for my bath, I gave him ten rupees for his effort. His eyes smiled. He said, "Why?" I said, "Because."

Neerag has a skinny brown body and drags his feet when he walks, but he has a sweet smile and black hair that flops across his forehead. He wears the same plaid button-down shirt, fit for a man three times his size, every day. And every morning, he's up at 6:30 to start his work. From what I can gather from a couple of broken-English conversations with him, Neerag came to Rishikesh ten months ago leaving his mother, father, and an older brother behind in his village (I asked if he has sisters, but ironically, he doesn't seem to know that word).

He claims that the man who runs this little place—six simple rooms and a small rooftop restaurant—is his uncle. Maybe this is true. But, any casual observer can see that Neerag really holds the reins, and hence, deserves to dub himself "Manager" with a straight face. He cleans the rooms, tends to the bathrooms, sets room rates, heats and ferries buckets of hot water (none of the bathrooms have hot water), takes food orders, busses tables, and does the laundry.

I'm not sure when he goes to sleep, but when I came out of my room one night after 11 PM to wash my face across the hall, he was curled on the floor in a pile of blankets. He sleeps on top of a woven mat, and under a wool blanket in the open area between the rooms. When I first saw him there, I thought about letting him sleep in my room on the floor. At least it would be warmer than the drafty hallway. But, I reasoned, it wouldn't do much good at all in the long term, and I'd probably set a bad precedent—from here on out he'd expect young American ladies to invite him into their rooms.

Neerag doesn't go to school. He doesn't play, and even if he did, he doesn't have any children to play with or the time to play. He sees his family two or three times a year. The opportunity for earning money here (and learning English from tourists, for that matter) is seen by his family as much more beneficial and lucrative than sending him to school which would cost money. I have come to learn that Neerag's story is not unique. Quite often, children are sent by their families to big cities like Delhi and Bombay, or touristy places like Rishikesh, to make money. Neerag is just one of several young boys I've seen slaving away during my trip.

I asked him, before I left the guesthouse, if I could take his photograph, but he refused. I don't think he didn't want to—I think he just felt too shy. He leaned against the wall, and he got very silent. I asked him one more time, but he shook his head, "No." I gave him an unnecessarily large tip, and he walked out quietly to get a broom to clean out my room and make it ready for a new traveler.

I wonder what he would rather be doing. Certainly, not this.

Monday, March 07, 2005

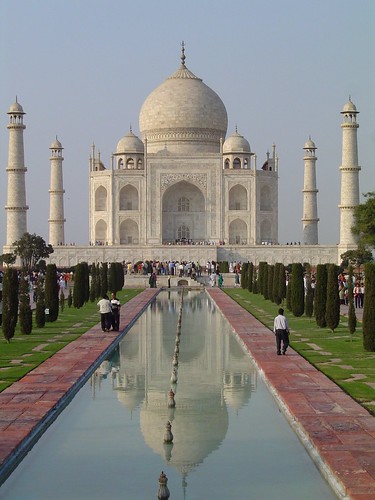

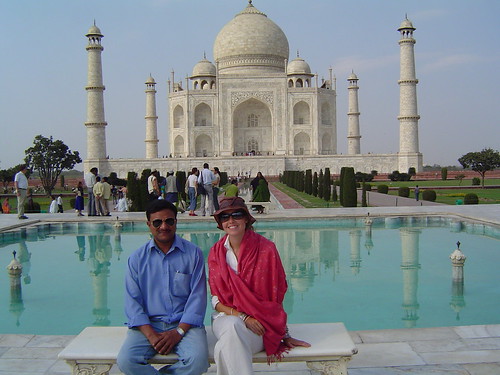

The Taj

I haven't read the Da Vinci Code. Although it has been on the bestseller list for ages, and numerous friends, from Israel to India to England, have given it positive reviews, I can't bring myself to read it. There's something about the fact that everyone and their mother has read it that makes me shy away from it. Call me Jonathan Franzen (the author who openly expressed disgust at his book, The Corrections, being placed on Oprah's Book Club list), but popular mass

fiction often doesn't live up to the grand reviews and adulation it receives.

Before seeing the Taj Mahal, I felt the same way—reluctant and a bit wary about this place that everyone raves about. Surely someone has hated it and just hasn't had the courage to say so. For some reason, visiting the Taj felt like more of an obligation than a treat, and I seriously considered just not going. But, when my friend, Dr. Steve (a doctor I met at the orphanage in Orissa) came to Delhi and offered to drive me to the Taj, I couldn't refuse. I'd have a friend to go with, get the Indian perspective, and skip out on the tourist bus filled with masses of camera-snapping white folks. Ideal.

Dr. Steve picked me up early and we visited the ruined city of Fatephur Sikri first. Quite fascinating old ruined city that had to be abandoned not long after it was built, because it's creator forgot that water was not readily available anywhere in the area. I have a feeling that it's best when you can spend a day or two walking around, but we only had a couple of hours so we made the most of it. It was stiflingly hot, so after Fatephur we broke for lunch, and recouped on masala dosas and sweet lime soda. Bolstered, we set out for the Taj.

To protect the Taj surroundings from the masses, its caretakers have blocked off the roads leading up to it so that cars and busses can't proceed. You can either walk up the long road to the entry gates, or wrangle a bicycle rickshaw, auto-rickshaw, or tonga--our choice--which is a horse drawn carriage. They aren't as regal as the ones in Central Park, but it's still quite nice to be pulled up the gates of the Taj by a white steed. After you go through the rigmarole at the gates, i.e. emptying your pockets, passing through the metal detectors, being patted down, etc. you can relax and prepare yourself. It isn't in sight yet, so you have a moment to collect your thoughts, and then proceed...ready?

Although I've seen pictures of the Taj many times, there is nothing like laying eyes on it the first time. Resplendent in its bright white marble symmetry, the sight of it opened my eyes wide, and lifted my cheeks a bit. I found myself drawing air into my lungs suddenly and had to sit down to take it all in. Four hundred some odd years old and it is still dazzling!

On a scale of Indian things, I'd say it's not quite as good as hearing 110 children praying at once, but much better than a camel safari, and on par with bathing baby elephants. It truly is the greatest monument to love, and if my significant other ever decided to build a magnificent marble tomb with exquisite inlaid semiprecious stones, and ornate carvings in my honor, I wouldn't object.

Up close, it's nice, too…but I wasn't as impressed by it as I was from afar. In fact, I was much more interested in watching the people visiting the Taj. There were busloads of children wandering about (imagine if this was your typical fourth grade field trip!), and they were the most entertaining. Dr. Steve and I spent a couple of hours taking it all in, and then headed out the front gates where hundreds more people were queuing up to see the sun set on the Taj. Truthfully, I doubt I'll ever go again—once was enough and the impression will, no doubt, last. But, it was most definitely worth the trek.

Note to self: go buy Da Vinci Code.

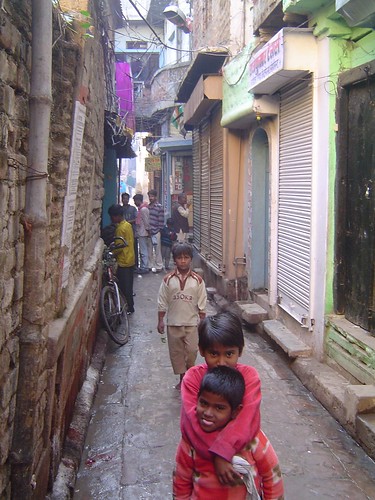

Boys of Bundi

A charming little group of naughty boys that surrounding me as I was walking around Bundi's fort. They didn't speak much English but they all knew how to request that I take their picture. Afterward, I showed them the photo, then asked them all for two rupees--my charge for taking the photo. We all had a good laugh about that...as they are usually the ones asking for small change.

Escher's Predecessors Lived in Bundi

One of Bundi's spectacularly deep stepwells. Several hundred years ago, townspeople would come to the well to bathe before going to the temple to worship. Back then, during the time of the maharaja, the well would have been nearly full to the brim with clean water. Now, the levels are very low. But, during the monsoon, the water rises considerably. This is one of a pair of matching stepwells near the vegetable market in Bundi.

Bundi?

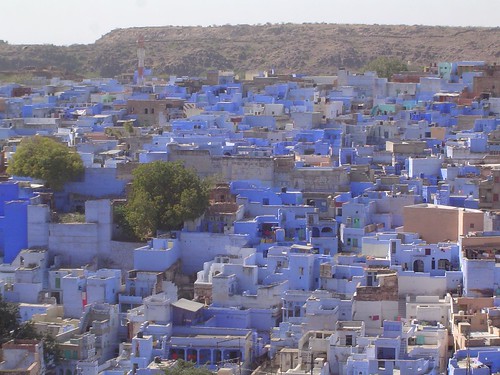

Driving North from Mumbai to Delhi, dodging decorated tractors, and being skirted by smoke-blowing Tata monsters, Bundi expects a double-take. Compared to the miles of hut-strewn villages and roadside chai stands, Bundi seems like a mistake. You look again—it's real. An architect's dream, it's golden-hued palace perches on the side of a hill, like a bird looking out from his aerie to the sights below. Above the palace, fort walls loom ominously at the crest of the hilltop, announcing that this place is worth protecting. And below, a miniature Jodhpur awaits, the houses glowing blue in the waning sunlight, smallish streets showing the way. Where did this fairytale town spring from, and why haven't I heard about it before?

Many people discover Bundi accidentally, as it's on the road between two of India's biggest cities. But, it isn't on a main train line, and the closest hub, Kota, is not much of a destination at all. Essentially, Bundi is rather out of the way, and, truthfully, that's probably for the best. Because it's off the beaten path, Bundi hasn't had seen the influx of tourists that some other places have; therefore, its residents are still quite innocent, the children friendly, the locals desirous to be of help. This is a far cry from some of the overrun areas where men and children can be overtly aggressive, either saying brash and inappropriate things, or patting down your pockets looking for treats and rupees.

I heard about Bundi from a Danish girl who hadn't been, but had met people who had. They had raved, and she told me she was going to go check it out. It sounded nice enough, so, on a whim, I scrapped my other plans to see Udaipur and Mt.Abu - well-known places in Rajasthan- €”and headed for Bundi.

The day I arrived, it was near sunset, and the first cutting of the mustard seed plant had occurred that day. Although it sounds rather romantic, the effect is rather dismal due to a small black fly, quite like a fat gnat, that finds this plant's oils irresistible. When the stalks of the plant are severed, the aroma of the oil fills the air, and billions of these little buggers smell it and swarm with the confidence of locusts, looking for a snack.

Even Indians, who usually seem impervious to the perils of their country (they drink the water, they eat the street food, etc.), were besieged by the flies, and walked through town covering their mouths and noses with the end of their saris or with a cotton handkerchief. I didn't notice the flies until I'd walked down the street about twenty steps. That was more than enough time for them to wiggle themselves into the wet corner of my eye, my warm nostril, my open mouth. So much for my flight of fancy, being footloose and spontaneous. What had I gotten myself into?

I harbored secret wishes that the flies would miraculously disappear by morning, but I heard from a local that they were here to stay. But, even with the little varmints buzzing about, Bundi charmed and wooed like no other place. Due to a vicious asthma attack I had had on a train across the desert, en route to Bundi, I wasn't able to move around much the first two days I was there. I would get winded just climbing a set of stairs, but, luckily, I found refuge in my hotel.

The Kasera Paradise just opened three months ago, having been refurbished after 80 years of neglect. It is a 16th century old haveli with an inner open courtyard that rises up the length of the four story building. On each floor, there is a window seat-cum-compartment (in India, everything is a something-cum-something) fitted with a thick mattress and cylindrical pillows. When you climb into the little cupola, you are essentially climbing into your own little nest that looks out over the town on three sides, through intricate latticework windows. Since I couldn't get around without coughing, sputtering, and wheezing, I soaked up the view and read or wrote in one of these little cubbies for the first two days.

When I did finally venture out into the town, I discovered sweet people, hairy piglets, a bustling vegetable market, young boys wanting to practice their English, and colorful neighborhood temples. Although moving about was tiring due to my weak lungs, the people and the atmosphere were calming and magnetic.

On my third day, I mustered the energy to go up to the palace. I'd spent so long looking at its frontis from the roof of my guesthouse, that I had started to think it quite ordinary, after all, its outer walls were only a matter of feet from the back of the Kasera. Other guests had told me that the palace had incredible frescos and an interesting stepwell where the queen once bathed. But, from my seat on the roof of the hotel, the palace looked like it couldn't possibly hold that much of interest. It looked pleasant from the outside, but I had no idea how huge it really was. Upon climbing the steep road up to the entry gates, I entered a new world. The face of the building never betrayed all that it held inside - €”the soul of this building was magical.

Walking through the grounds, it was no stretch of the imagination to feel like an archaeologist discovering this place for the first time. Unlike historical sites in some places, particularly London's palaces or Edinburgh's castles, there were no guards protecting certain areas, no red ropes cordoning dangerous stairwells. At times, it would have been nice to have a guide to explaining the significance of a creamy white marble room or the meaning of a mirrored turquoise and gold wall painting; on the other hand, it was incredible to roam around and explore at will. In America, this place would be a lawsuit waiting to happen, but for the wannabe explorer, it was heaven. Gingerly crossing over landings with gaping holes, lowering myself into dirt covered rooms, winding up tall curved stone stairwells, peering out of blue and red stained glass rooms - €”it was the find of the century. And it was all mine. Three hours of poking about, opening heavy wooden doors, entering bat filled rooms, finding myself in the marharani's dressing quarters, in the soot-filled cooking rooms, in an ancient lavatory (with a view!).

As mentioned above, most often, visitors to the palace gush over the well-preserved wall frescos. Maldives green, peacock blue, poinsettia red—the colors and the images are remarkable. But, I was more mesmerized by the incredible architecture. So many rooms, and split levels, narrow staircases, secret rooms - the design is ingenious and extremely complex - and an absolute dream to explore!

I'm told that we have this place, Bundi and its mystical surroundings, to thank for the Jungle Book. It's said that once upon a time Kipling came here and stayed in the fort and explored the palace and a nearby reservoir. It inspired him to create Mogli and his various jungle friends. Not surprising since a wildlife sanctuary, the Ranthambhore National Park is just 45 kilometers away.

Unfortunately, I didn't make it to see the tigers and bears, oh my. I spent the rest of my days climbing down deep stepwells, exploring the fort, and visiting a nearby cave temple where the monkeys seem to worship Shiva as much as the local people. Since I left there, I've had conversations with several Indians and foreigners about where I've been. Everyone gives me a quizzical look. What's in Bundi? Where is it?

I'm not telling.

Saturday, February 26, 2005

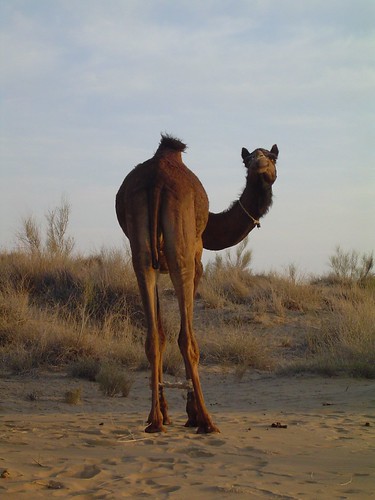

Jaiselmer, Part 1:Camel Safari

I admire the clever soul who conjured up the idea to tame camels and

ride them—the fact that they are built with a huge hump in the middle

of their backs was no obstacle. I'd saddle up a water buffalo before

I'd think to reign in a camel. But, some turbaned mustachioed man,

tired of traipsing through the desert on foot, invented the camel

saddle, and so, a couple of days ago, I found myself riding into

rippled sand dunes on Pappu, my trusty camel steed, listening to Jerry

Jeff Walker as an invisible chariot pulled the sun across the sky.

I was truly craving Sangria wine by the time we arrived at our

campsite—simply a slight depression in the sand to protect us from the

night winds that gust across the dunes. I doubt I've ever been as

cold, sleeping under a half moon and the Milky Way on a firm bed of

sand. Although I was well equipped with three heavy wool blankets,

they didn't do much to shield the body from the invasive chill of the

desert night. The beer probably helped more than the blanket.

Bear in mind, this was no luxury camel safari, so the thought of

drinking a cool beer had not entered my mind. Some might call it

"roughing it," although it felt a bit like summer camp. We were a rag

tag bunch, six young foreigners paired with two camel guides, and when

we reached our camping spot, instead of relaxing, we were ordered to

go gather wood. Hmm. You get what you pay for, I thought. The sun

nestled itself on the horizon, rays fanning out across the sand, while

the we foraged for wood for the cooking fire and the camp fire.

After night had taken us captive, and before the moon had appeared on

her grand stage, I heard the jingling of a camel bell coming towards

us. I tapped Ellen, a French girl and told her that I thought there

might be something out there. We became still for a moment, and

squinted into the darkness. Out of the black hills of sand rode a

white clad, orange-turbaned man on a palomino camel. Perhaps I've

seen one too many desert/warrior/attack movies, but I immediately

pictured us surrounded by crazy Indian nomads on all sides.

Thankfully, this guy was alone, and miraculously, he bore gifts of

beer, crème biscuits, and chewing gum. This must be the modern mythic

lone ranger—the desert camel-man who arrives unannounced bearing beer

and a bright tangerine turban.

A bottle of beer cost as much as one night's stay in my hotel; but, at

$2, I guess one can't really complain. It was a nice treat, and may

have staved off my demise during the chilly desert night. The next

morning, we were treated to a breakfast of wheat porridge, laden with

crunchy sugar crystals, hard-boiled eggs, toast with jam, and chai,

sweet and milky. Not bad for a cheap camel safari. By nine we were

seated back upon our camels and went trotting across the dunes to our

next destination.

Jaiselmer, Part 2: Desert Festival

On the safari, our camels knew the way to go out of habit, so steering

them was not an issue. Pappu bumped along, following the trail

without a nudge or a pull from me. In actuality, though, camels

either have a poor sense of direction or don't respond well to

steering—as was evidenced by the camel races I observed when I

returned from the camel safari.

When I arrived back in Jaiselmer, the town was in the midst of a three

day "Desert Festival," which, I learned, is the highlight of the

season here. The festival features a "Mr. Desert" Contest, a

moustache competition, a turban tying competition, camel races, camel

decoration (or sexy camel contest, as I call it), and camel polo.

They also have tug-of-war, in which they pit brave foreigners against

Indians. Both men and women compete, but in separate rounds. I am

proud to report that the foreigners won both competitions!

I've jogged my memory, and I can't recall that camels have any

predators—who would want to eat a camel, they seem like they would be

chewy and tough?—so there's little reason for them to be able to run

quickly. I couldn't convince Pappu to break into anything more than a

hearty trot, and made the assumption that he just didn't have a higher

gear. I was proved wrong, though, at the camel races; they must have

something to run from, because when they reach full speed, their legs

go flying into the air in a tumbleweed of activity.

About five camels race each other in each heat, and they are given a

wide berth: the track is an open field; they merely have to make it

from one side to the other. However, this is no Kentucky Derby; upon

the ringing of the start bell, the camels are off and running in

whatever direction they choose, with no concern for their rider's

instructions. I immediately realized why the guards had been so

adamant about clearing the space around the field. They bust through

crowds at full speed, or go running down the road, careering sideways

off into the distance. Some break into a full gallop, but some, like

Pappu, preferred to trot, allegro!, jarring their rider along.

Determining the winner is simple: inevitably only one or two camels

make it across the finish line, anyway.

Camel polo is just as entertaining. The game is played the same way

it is with horses, except the field is smaller, made of sand, and the

sticks are longer. Whereas horses who play polo seem to know exactly

what they're doing, and will make an effort to get to the ball and

position themselves in a convenient way, it appears that camels

haven't quite caught on. What results is a hilarious spectacle of

legs, bendy necks, and dust, as riders do their best to make contact

with the ball. The Indian army competed with a team adorned with pink

and green saddle blankets. I'm pretty sure the army won.

The Bad and the Ugly

If only India was made exclusively of soft-trunked elephants, limey

green parrots, and sweet faced children...alas, it has its dark

moments, too. I'd be lying if I left everyone with the image of India

as pure beauty. What follows are the elements about which it is not

so easy to wax poetic.

1. Excrement. Sometimes, as much as one wants to look up at Dutch

colonial houses, finely carved cupolas and monkeys leaping from roof

to roof, it's best to look down. Low-flying meteors of every

consistency smash into the ground, and remain there until a sweeper

decides to remove them. Therefore, obstacles to avoid include poo

from every creature roaming about, including but not limited to, big

humans, small humans, birds, monkeys, pigs, camels, elephants, horses,

water buffalos, dogs, cats, donkeys, and of course, cows. Often,

dirt, mud and dung are indistinguishable and combine in a nutella

layer on the entire walkway, forcing one to pick and choose as best

one can, the lesser of all evils. Excrement.

2. Smells. The above listing contributes to a marvelous array of

tremendous odors that it is best not to breathe. Smells.

3. Dogs. There are so many people and cows to take care of in India

that dogs tend to be overlooked. You have never seen dirtier, more

flea-bitten creatures. They live on the scraps left out in the

streets, and they inevitable sleep in piles of trash, because it

smells nice to their wet noses and seems cozy. Due to their poor

diets and exposure to unimaginably sordid elements, they often have

nasty skin diseases which leave scabby welts and rob them of their

fur. Many are just bags of bones, and sometimes those bones have been

battered by moving objects or bruised by cruel children. The ones

that survive brutal collisions usually wear their injury for life. One

leg may curve completely under the body—after breaking into three

pieces there was no one to set it straight. The spine may twist

grotesquely. The jaw may be misaligned. Where is the Mother Theresa

of the dog world to help these poor brutes? Dogs.

4. Barking dogs. Where there is one dog, there are many others. When

one dog finds occasion to bark, the others follow suit in a symphony

fit for no one. The most opportune time of the day to hear a dog

symphony is when you are asleep. Anytime from midnight to 4 AM seems

to be fair game in the dog world…and completely unavoidable in the

human world. Barking dogs.

5. You pay for what you get. Hotels in India are cheap. Decent

establishments cost anywhere from $2 to $20 a night. I have never

spent more than $16 a night, and I have stayed in some nice places.

That said, a $4 hotel room can be expected to come with the following:

a bed. Consider yourself lucky if there are sheets, a ceiling fan, a

telephone, a Western-style toilet, and hot water. You've won the

lottery if the room includes a television, toilet paper, soap, and a

window. Most often, the bed is hard enough to make you turn yourself

like a rotisserie chicken during the night to avoid bedsores, and the

room is lit with oppressive florescent light bulbs. You pay for what

you get.

6. Laundry. Indian washing machines are called dhobi-wallahs. A

dhobi, more often than not, is a small bony man who sees to it that

the dirt your clothes have ingested is expectorated. To do this, he

beats the dirt out of your cloths in the closest large body of

water—if it's a nice establishment, then he'll use water from the tap.

If the Ganges is available, he'll use that. If standing green pond

water fitted with a layer of protective moss is nearby, he'll use

that. To be fair, the dhobis do a tremendous job of removing dirt

from clothes. However, the drying process tends to undo this newfound

purity. Clothes are dried on shrubs, in dirt, on highway medians, and

rooftops—anywhere the sun has decided to cast its rays. It's not

unusual for a shirt to come back with new smells from sketchy water or

new stains from the drying process. Laundry.

7. Kitchens. It's best to avoid them. Better to imagine that your

food has been created by a genie in the backroom, untouched by no one

and nothing. Upon entering a cooking establishment, one realizes that

conditions are never sanitary, and sometimes quite putrid. Kitchens

develop an earthly, rotten smell over time, and the walls are usually

covered in black soot from the cooking fires. Space is at a premium,

so it is not uncommon for a plate to be set on the floor before

something is ladled onto it. Water is also at a premium, so dirt or

sand is used to scrub dishes instead. The good news is that the raw

materials (the fruits, vegetables, rice, lentils) are always fresh;

the bad news is that the oil used is sometimes rancid. Ugh.

Kitchens.

8. Beaches. Are beautiful to look at, but hazardous to go near. Many

Indian males and children have adopted the ocean as a personal bidet.

Best to look and not touch—from afar. Beaches.

9. Bugs. Are everywhere. They particularly enjoy mouths and eyes,

and love to bury themselves in food. If one finds a fly in one's

soup, protocol entails removing the offending critter, and continuing.

It's not that unusual and therefore, not something to draw attention

to. Bugs.

10. Sketchy Indian Men. Like bugs, they are everywhere. Like

beaches, its best to stay away. Like dogs, they feed off each other

and can be offensive and noisy. Like excrement, they are unavoidable.

Sketchy Indian Men.

Everyday I wake up and marvel at the beauty of India. And, there are

so many things to love about this place that it is easy to look past

the less wonderful aspects and find magic. But, it wouldn't be right

to speak only of the lovely winding walkways, and the sonorous voices

of children. India is everything, the good and the bad: from the dung

to the flowers, the dogs' barks to the children's voices, the

mosquitoes to the electric birds. Perhaps flowers wouldn't be so

bright and narrow lanes not so magical if these extreme contrasts

didn't exist. To find the beauty, one must accept it all.

If I Were a Camel

If you close your eyes while you're ambling along atop a camel, it is

easy to imagine that you and this prehistoric beast—doubtless they are

the closest living relative to the brontosaurus—are one. Your legs

are now eight feet long, an extension of your human pelvis…if runway

models could strut this way, fashion would never be the same. Atop

your camel neck, sits your camel head equipped with floppy lips, Betty

Boop eyelashes, and a calm Buddhist demeanor. Like the snaky eye of a

submarine, you take in your surroundings, but don't deign to react to

anything—it's all zen, baby. When it comes time to stop, you groan as

you lower yourself, accordion-style, to the ground, folding your long

legs under you. As night falls, you are given freedom to roam into

the desert, far from the turbaned man who tamed you, and even farther

from the saddle he created to make you his beast of burden. For a

couple of hours, you are the desert denizen you once were.

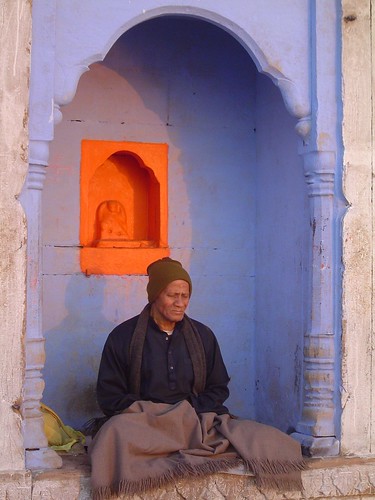

City of Blue

Am sitting on my little porch in Jodhpur watching the light on the

blue buildings as the sun makes it's way to the other side of the

world. It is spectacular. Not only is this place beautiful, but you

can watch life being lived on other rooftops: children playing, old

men tinkering about, women sorting vegetables. I wonder if they know

that most places aren't blue, and that in most cities you can't jump

from rooftop to rooftop, like the monkeys here do.

Wednesday, February 16, 2005

Getting Lost in Varanasi

I am still not entirely sure what happened to me yesterday in

Varanasi, a mystical, ancient Indian city perched on the banks of the

Ganges River. Varanasi, previously known as Banaras and Kashi, is one

of the holiest places in India, where many Indians come for a dip in

the water of the Ganga, as it is said to wash away all sins, and many

Hindus come to die, as meeting your end here gets you a free pass out

of the cycle of reincarnation. From a boat in the river, one can look

up at the ghats, the steps that lead down into the water, and see men

and women bathing at any time of day; Indian sadhus (holy men)

chanting; toned yogis doing sun salutations; and foreigners taking it

all in. It is, altogether, a completely overwhelming and magical

place.

It's easy to get lost in Varanasi's Old City, where the streets wind

every which way, and most are only four or five feet wide. It seems

that when they built Varanasi, each person desired that his house to

be as close to the Ganges as possible, so they are stacked on top of

one another, back to back, and side to side, which creates a dizzying

effect for the visitor. At times, it seems that they should have just

built the entire city in the middle of the river…it probably would

have been simpler.

Usually, when I roam around a place like this, I put my headphones on

to avoid the touts and numerous men and children who approach me. In

Varanasi, I did the same, and with music blaring, I set off to get

lost in the congested, twisted walkways. It's the only way to truly

get a feel for things in Varanasi, and if you wandered around with a

map, you wouldn't do yourself much good anyway as nothing is

signposted. Somehow, in a span of 45 minutes, I managed to come back

to the same exact intersection three times, each time from a different

lane. By the third time, I was laughing out loud at the insanity of

the situation and shopkeepers were smiling at me with knowing looks.

I finally extracted myself from that part of the city and made my way

down the river to Manikarnika Ghat, the largest burning ghat in

Varanasi. As mentioned above, dying in Varanasi is the ultimate

end…the linchpin in the cycle of reincarnation that effectively frees

a person from the bonds of life and death. At Manikarnika Ghat,

bodies are cremated every day, first wrapped in bright red and gold

cloth, then carried into the Ganges to be bathed, and afterwards, put

on a pyre and burned. Foreigners can watch the process, but if you

do, touts constantly approach you, requesting money for the privilege

of watching the process unfold. Unfortunately, these touts have no

relation to the dead…they just want to make money off of clueless

foreigners.

So, for several reasons, I didn't remain at the burning ghat long. For

a foreigner it is something completely different and quite magnetic,

but each ceremony is, of course, not just for show. A family sits

watching their loved one turn to ash. It must be disconcerting for a

family to feel as if foreigners are always silently watching this

custom.

I left the burning ghat after a couple of minuets and perambulated

skinny streets lined with tiny shops selling packets of this and that,

looking for a main road. The shops are so small and the streets so

narrow that it gives the viewer an Alice in Wonderland effect. The

ceilings and walls are just inches away from the shopkeeper's head—you

wonder how they don't go crazy perched inside all day. In some spots

in the lanes, you can reach out and touch the walls of houses on

either side of you.

I never found a main road. I walked up steps, through covered

passageways, around shadowy corners, and down a lane where I was

suddenly confronted by eight armed police officers. They searched me

and my bag asking for a camera and looking at my mp3 player with

interest. Luckily, I hadn't brought my camera with me, and I explained

that the mp3 player was just a walkman. A couple of feet ahead I

noticed an ad hoc metal detector, and wondered what I had gotten

myself into. It seemed I had stumbled across a secure zone; but, I

didn't have the heart to indicate to the officers that I had no idea

where I was or what I was doing. After they had checked me out and

realized I was no one of interest, they waved me through.

There is a scene in the French film, Amelie, in which the title

character, played by Audrey Tatou, guides an old, blind man through

the streets of Paris. She notices him struggling, and decides to take

him by the arm and guide him to his destination. As she rushes him

through vegetable markets, past chickens, in between children playing

in the street, she narrates the scenes around them, so that he can

experience everything as if he has eyes to see. By the time Amelie

takes leave of him, the blind man is completely dumbfounded, not quite

sure what has just happened, but certain that for those brief moments,

an angel was sent down from above. An old man adopted me in the very

same way after I passed through the metal detector.

I had only wandered a couple of yards into the protected area, when a

hunched man with a short growth of grey beard, clucked at me and

motioned for me to join him. I am sure I looked lost; I was taking

everything in. There were several little makeshift shops selling

bangles and brass pots right when you entered the area, and behind

them, a tall chain-link fence rose twelve feet high, topped with

tumbleweeds of barbed wire. Behind this were thick trees and behind

them, the bluish spires of a mosque peeked out. Perhaps this

explained the tight security? I had no idea what the little man

wanted, but I walked to him and without pause he started chattering

away in broken English about my surroundings, starting with a statue

of a giant red cow.

We were only together for about three minutes, but in that time, I was

blessed twice, taken into the inner sanctum of a sacred Hindu temple,

paraded past more gunmen, and led through claustrophobic market shops

where bright flowers, sour yogurt, intoxicating betel nut, silk saris,

and golden fabrics were sold. I ended up in a completely different

place than I had begun, the old man disappeared without a word, and I

stood flabbergasted with orange and red powder on my forehead, and a

bright-colored string tied to my wrist. What had just happened?

Part of me didn't even want it explained. The chanting of the Hindu

worshipers I had witnessed inside the temple still rang in my ears,

and I still had no idea what all the security was for—I hadn't even

see the mosque!

I found the nearest exit, and walked past the guards back into the

narrow streets, having no idea where I was. Eventually, after an hour

or so, I wound back to a descending street with a huge black cow

lounging about, nearly blocking the lane. This was a signpost I

recognized; I had reached my hotel.

I learned later that non-Hindus are never allowed into Vishwanath, or

the Golden Temple, the most sacred Hindu temple in Varanasi. I

shouldn't have entered, the man shouldn't have blessed me, and I

probably had no right to be sporting the orange string around my

wrist. I should have paid the old man for the experience—but he was

aiding me in breaking rules I didn't even know about! I should have

known that the mosque is the second target in line for desecration by

the Hindu BJP party because of the tense situation here.

According to my guide book, the Vishwanath temple has been in Varanasi

since 1776, but there were once quite a few other Hindu temples in the

area. However, Muslim invaders routinely destroyed them on raids, and

the Alamgir Mosque erected there now is a site of contention for right

wing Hindus. The BJP would like to see it destroyed so that the Hindu

temples that were once there can be rebuilt; hence the high security.

I felt a bit sheepish after I read all this, and was quite furious

about the old man taking me unawares into the temple. But, the memory

of the experience, in retrospect, is like tasting alcohol for the

first time—you know it is forbidden, and the taste makes you cringe,

but in spite of this, you are thirsty for more, and the memory of the

taste makes your mouth wet.

I've talked to other foreigners since leaving Varanasi, and asked them

if they went into the area around the mosque or visited the Golden

Temple. Each gives me a blank look and a shake of the head, no. None

of them even saw the police officers who were crawling all over the

area. Sometimes I wonder if it was all a dream.

The Orphanage

So, the journey continues…in uncharted territory. Today (February 2),

I left Southern India and headed north and east to Orissa, a state

considered to be the second worst off in the country (Bihar is the

first). Flying into Bhubaneswar, the Orissan countryside reminded me

a bit of West Texas—if you've never been, just imagine a wide, flat

expanse of dust. But, Bhubaneswar, Orissa's capital city, was a

pleasant surprise, lacking the congestion of Chennai, and oddly

relaxing. Everyone I've spoken to has warned me to stay away from

Orissa, as it is a backwards place. But, if the cows are any

indication, this place isn't nearly as bad as the rest of India

thinks; they are all quite robust and have a certain smugness about

them that you don't see in South India.

Cuttack, a dustbowl just half an hour from the airport, was my final

destination. It will be my base for visiting a nearby orphanage in

Choudwar called The Servants of India Society, just 8 km away.

Before I ever set foot in India, I jotted down notes on how I imagined

this place would be, just to be able to compare my expectations with

the real thing. The general hypotheses were as follows: "Cuttack and

the orphanage are bare and dusty. The kids are overwhelming and

exuberant. There, you never feel clean, but always feel joy."

I would describe the orphanage as spare, but Cuttack, despite prolific

clouds of dust, is a market town filled with people, small shops, and

busy lanes—anything but bare. Having visited the children at the

orphanage briefly this afternoon, I can attest that they are indeed an

overwhelming lot when they have you surrounded, but their smiles,

their little bellies, make you want to take them home with you.

As the sun went down in Choudwar, a rather smarmy fellow who works at

the orphanage, invited me to join them for prayer. They all sit

together, both the children and the caretakers, in one big room on the

floor. At the front of the hall hang pictures of whichever god you

pray to, be it Krishna, Ganesh, Jesus, or Sai Baba, an Indian man with

copious amounts of facial hair. Incense, which I don't usually enjoy,

burned in a little shrine below the posters, and the wafting scent

seemed to fit the occasion perfectly, blending into the little voices

that soon began changing Om.

Om led to a slow song, which was followed by a faster song, and an

even faster one after that. Before I knew it, my fingers were tapping

my legs to the beat. The sound of one hundred and eight children

singing in Oriya is electric—like all of the stars in the sky

twinkling at the same time, or the feeling you get when a cool breeze

rushes at you from nowhere on a hot night. Their voices entered

through my ears and scurried with little feet into my bones and eyes,

and into my heart, which normally beats as if it is taking stairs one

at a time, but jumped as if I were climbing three in one bound.

I'm not sure if I was supposed to bow my head the entire time, but

like a kid playing hide and go seek, I couldn't help but peek at what

the children were doing. Some sang with their eyes open, but one

little girl closed hers intently, and holding her fingers in two

mudras as if she were meditating, she sang loud and clear. A boy,

with striking blue-hazel eyes, light olive skin, and coal hair, looked

straight ahead at the boy's head in front of his, without expression.

I wanted to bottle this sound and capture these faces forever. I

wanted to put them all into a little book that I could open on any

given day and see and hear it all over again.

Morning in India

Early morning in India happens to be one of the most curious times.

Under a blanket of black, to the crooning of insomniac birds, life

begins while the town itself slumbers. On city sidewalks, groups of

fifteen or twenty men squat together organizing the day's paper,

putting each section in its place and bundling stacks together. The

machine you thought was made for that purpose does not exist here.

Scraggly dogs, who have enjoyed a nice sleep in the middle of the road

where the asphalt cools, are forced to drag their bruised, rag-tag

bodies over to a pile of trash for breakfast.

Chanting comes out from a nowhere, from side streets, behind low

houses, a guttural wailing whose vibrations are so low it's rather

soothing. Church doors open for those who want to start the day in

prayer, and usually church halls fill with standing parishioners,

women shrouding their black hair with the long end of their sari, men

extending their hands to the sky. Hindu shrines are blessed, their

fires lit, flowery garlands placed with care around a stone Ganesh's

shoulders.

Those who seek a physical awakening—the men and women who slowly jog

or walk with arms swinging—get their morning exercise while it's still

cool. Butchers, perhaps so the meat won't have the chance to stew and

stench in the heat, hang giant carcasses in silver meat hooks and

begin carving the spread legs of some recently (we hope) deceased

beast. The sun won't rise for another hour or so, but the heartbeat

of the city has already quickened.

Later, after the sun peeks over tall whitewashed walls, the sounds are

sharper, more laborious. Dhobis begin the washing with a rhythmic

slap-slap-slap, and sometimes, if you're lucky, you'll hear the sound

of the daily coconut harvest: a rustling and then a crash. A monkey

man scales the towering, spindly trunks of coconut palms with his feet

and a long rope. Using a machete, he hacks the fruit, carefully

protected by a thick green hull, away from the fronds, and they go

flying to the ground, gravity happy to have something to act on.

Store fronts are swept clean by women bent over at the hip—yogis can't

even do this move—and shop owners raise their awnings and grills. The

birds' croons have turned to squawks and cooking fires are hot. The

day has officially begun.

Thursday, February 03, 2005

Saris for Kasimedu

Last night, in the cool darkness that settled on Kasimedu just after

sunset, I distributed saris and lungis to 100 of the neediest families

in northern Chennai. This was my second visit to Kasimedu, a rundown

kuppam (neighborhood or area) in between the ocean and the one room

houses that wend their way through narrow lanes to the main road.

These people have lost everything. The tsunami struck down their

makeshift huts, shoddy to begin with, and then, after receiving aid

from the government, a fire swept through the encampment charring

everything, leaving nothing but dried out boat carcasses and piles of

ash and bits of cloth.

The stories the women and children told me on my last visit brought me

to tears--not an easy feat. I had been to four or five fishing

villages already, places that had lost hundreds of people to the wall

of water that descended upon them. These other places had sustained

quantifiably more damage, but they seemed to be coping. They were

rebuilding houses, had clean water from Unicef, and food from private

aid organizations. The children laughed and played in the street.

The women presided over their cooking fires, happy to have something

to do. However, the desperation of the women in Kasimedu was palpable.

They clustered around me, each talking over the other in an effort

to have her situation understood. This was a place where no one asked

me for money, they only motioned, bringing hand to mouth, that they

were hungry.

The smell of Kasimedu stayed with me after my first visit. Walking

through the black, ashy encampment, leveled by water, then dried by

flames, a deep, earthy acrid smell filled the air. When the village

women and children surrounded me, I was tempted to cover my mouth and

nose to shield the inner membranes of my orifices from the

stench—sweat mixed with dirt, dead fish, burned plastic, human

waste—all of it muddled together to create a foul odor that had seeped

into their hair and soiled their saris. How do they live here? The

wafting smoke from a Gold Flake cigarette was welcome. I inhaled the

second hand fumes heartily, just to have something to mask the smell

around me.

Two days before I was to leave Chennai, Narayan asked me what I wanted

to do about the villagers in Kasimedu. Did I want to go see them

again? Did I want to give them anything? I did, but I wanted to give

them things they could use. We needed to ask them what they wanted

first. Narayan went to work, and found out, through his fisher-friend

Patrick, that that day two foreigners had visited the kuppam and

handed out rice and kerosene. The people were so desperate for

supplies that they mobbed the donors, creating mass confusion. The

need for food overwhelmed the villagers and they grabbed and

quarreled, knocking things out of the donors' hands, some people not

receiving anything at all in the melee.

I wanted to avoid this situation. Having been in the middle of groups

of villagers tugging on my shirt, touching my hair, asking for money,

I knew that this could be a recipe for disaster. So, on my last day

in Chennai, Patrick devised an entire system to ensure that everything

would run smoothly. He found out through the head of the fisherfolk

that they needed clothing. Most women only had one sari, and some men

did not even have one lungi. We would have local men hand out tokens

to the neediest families, and later that night, they would bring a

token to a meeting point, and would be given a bag with one sari and

one lungi.

To me, a sari has always seemed like ceremonial garb. If I were to

buy one, I would only wear it to a wedding or a formal celebration.

But, here a sari is everyday attire. A poor woman will wear hers

during the day, and use it as a sheet at night. The same goes for a

lungi (very similar to a sarong, but worn exclusively by men). Men

wear lungis day and night, wrapping one around their waist to make a

long skirt, and looping it up, when mobility is needed, into what I

would call a mini-skirt.

Late in the afternoon, Narayan, Patrick, and I went to a wholesale

textile shop to buy the material. Fortunately, the shop owner gave us

a great deal because he knew that the material was intended for

tsunami victims. He sold the saris for Rs.60 and the lungis for Rs.

45. That's $1 for the men's piece, and $1.50 for the sari. My budget

only allowed me to buy 100 of each, but Patrick said anything would

help.

So, we loaded the material into a rickshaw and hustled back to the

meeting spot, an empty parking lot behind a rice mill. Patrick picked

this out of the way location so that we wouldn't get mobbed by the

general population. Overall, the system worked. It wasn't a great

time to hand out the goods, because it happened to be the time when

women are supposed to be tending their cooking fires. But, about 75

women and men showed up to accept the outfits. The rest will be given

out this morning.

Originally, when saris were suggested, I didn't like the idea. It

seemed like we'd be giving something superflous. But, Narayan

reminded me, "Food, clothing, shelter." They received food. There

was no time to build shelter. Clothing would have to do. I hope it

helps.

I Think I'm in Love

I've fallen in love with another man. He's a bit older than me, but

he has a fantastic smile, and wrinkles in all the right places...just

kidding. But, seriously, does this little old fisherman not have the

warmest face you've ever seen?

Wednesday, February 02, 2005

Tsunami Story: Sokktikuppam

On the first day of February 2005, I found myself standing in a palm

grove drinking juice straight from a green coconut on an island off

the southern coast of India. Sounds idyllic, even sybaritic. Walking

around the little island of Sottikuppam, 250 km south of Chennai, it's

easy to miss the telltale signs of tsunami devastation, and only see

the beauty here. After disembarking from a small ferry, one walks the

sandy lanes lined with blue and lemon pastel houses past the pink and

green fishing nets drying in the sun, hearing laughter flow out of

school windows, and seeing fisherman sit in the shade playing cards.

However, if you continue walking the short distance to the beachfront

on the eastern side of the island, you'll find wreaked fiberglass

fishing boats, gaping holes in their sides, and long spindles of wood

that used to form a catamaran, useless now. There are fishing nets

bundled together at the base of coconut trees, too torn to be of any

good for catching fish, and on the southern end of the island, there

is a gigantic beached oil ship unmoored from a harbor near

Cuddalore—all a result of the violent and unruly tsunami that struck

on December 26.

This is my second visit to Sottikuppam in two weeks. I've come back

to this place after visiting several other tsunami affected areas in

Tamil Nadu and Kerala. The people and the stories in Sottikuppam kept

coming back to me on my travels—I needed to come back to them to see

how they were faring. Consider me a concerned citizen of the world. I

am not a reporter or a government official, not the leader of a

prestigious aid organization. I am a lover of India and its people,

and due to a fundraiser I held before I came here, I have a small sum

of money that I would like to give to tsunami victims that need aid.

Sottikuppam interested me from the beginning. Since it is an island,

its people are both protected and isolated from mainland issues. This

can have positive and negative effects. For example, in several

places I visited, there were rampant tales of corruption: fisherboat

owners keeping aid for themselves, instead of disseminating it to

laborers that run the boat; a social welfare officer taking money

meant for orphans.

On the contrary, Sottikuppam is devoid of any air of corruption. From

my first talk with the village chief, V. Raman, and the elders, there

was a sense of community, a gracious attitude, and a general feeling

of goodwill. It seems that being an island, a contained community,

has made them wholesome and dependent on one another; unfortunately,

it has also kept them from receiving aid quickly and effectively.

This island of 1,780 lost twenty-five people in the tsunami,

twenty-three of which were children. Any loss of life is a tragedy,

but admittedly, Sottikuppam didn't lose as many people as Cuddalore or

Nagipattinam. For this reason, it seems, the island hasn't made

headlines. But their needs are just as sharply felt as other fisher

communities. When rice intended for them is taken by selfish

mainlanders, the 400 surviving children on Sottikuppam go hungry.

When the Collector appears and exhorts fisherfolk to go back to sea,

the fisherfolk can only count on each other when a boat is overturned

and a man is sent to the hospital. When sacks of government-given aid

are opened to reveal kilos upon kilos of yellow, soiled rice, the

elders have to find another way for their people to eat. When

villagers hear of government grants and additional aid, they are the

ones left waiting with nothing to show when those promises never

materialize.

The first time I visited the island people, their situation was dire.

More than three weeks had passed since the tsunami hit, and they had

only received standard government aid. Other areas were besieged by

help from Unicef and other big name organizations. Sottikuppam had

been overlooked by private donors and NGOs and as a result, they were

struggling.

My most recent visit was more encouraging. Members of Development of

Humane Action (DHAN), an organization based in Madurai, have adopted

Sottikuppam and committed themselves to repairing all boat engines and

damaged boats here. This move alleviates some worry and financial

strain, as some of the boats will cost upwards of Rs. 20,000 to

repair. Other organizations have given good quality rice, cooking

utensils, bed sheets and saris. All supplies offered are divided

equally amongst the two thousand villagers, which means that 750 kilos

of rice will only last one day.

For now, life is still being lived day to day. A cooking fire burns

continuously at the small school, where communal meals are served.

Fishermen bide their time under palms, waiting for the chance to

resume their diurnal routine. Village leaders meet regularly to

discuss ways to get back on their feet. The situation is tense, but

the pace here is slow and relaxed. The government has given as much

as they can. One or two organizations have stepped up to help. But,

how many other villages are suffering in silence? How many other

fisher-families must wait for their boats to be made sea-worthy? How

many people are dependent upon the kindness of strangers?

Ice Cream Social

Yesterday I walked to Marina Beach in Chennai with Narayan and a

friend of his known as Crabman. Marina Beach, a long stretch of sand

and water, is home to several hundred slum dwellers. It was the

hardest hit area in Chennai; where one house remains, another two are

gone, reduced to rubble and debris. Chickens, mangy dogs, skinny cats

and the occasional puppy wander the streets, as people go about daily

life. Posters have been hung on walls still standing, as a reminder

and remembrance of people lost to the tsunami.

Some families here lost everything--their homes, fishing boats,

fishing nets, and often, a family member. Yet, smiles prevail. I was

welcomed by curious looks and many women eager to explain what

happened. And, the children demonstrated their resilience, following

us through the dusty lanes laughing and saying the handful of English

phrases they knew, "Hello. How are you?" "Tata! Bye!" "Photo?" The

girls in this photo had stopped in the street to enjoy an afternoon

ice cream cone. They erupted in laughter when I took their picture,

and were so giggly that one knocked her scoop into her hand--more

laughter ensued.

The women told me that the waves came in the morning around 8:30 AM

but did not subside as one might think. The water rose up the beach

quickly and then remained there for over a day at a height of over two

feet, filling the bottom floor of houses, and creating a haven for

bacteria and disease. This slum sits on the ocean, and is abutted by

a river on one side, so when the water finally receded, dead bodies

lay on the river embankment--a grim reminder of days past.

The Indian government should be commended for their handling of the

situation. Most higher-upsI have spoken to have said that their

people have been taken care of, given 4000 Rs. (just under $100), new

boats and nets, and food and clothing. When I ask if there is more

that can be done, and I explain that many private donors in the US

want to help, I am rebuffed. "Everything has been taken care of,"

Crabman told me with pride.

Whether that is true has yet to be determined. It is the

responsibility of interested donors to be persistent and ask the right

questions of the affected people--not the government officials--about

their needs. The people have received the aid they need to make it

through the coming weeks, but after that who will support them?

Bathing With Elephants

Knee deep in river water, scrubbing a baby elephant with a coconut

husk, I paused to pull out my camera. One of the other elephants was

making a run for it, and his trainer was trailing behind him, holding

on to his tail to no avail, as it is much like trying to stop a moving

vehicle with a thread. Eva, the four year old female, won this tug of

war, but she didn't stray far. It seems she just wanted to have a bit

of freedom before returning to having her body scrubbed. I'd liken it

to a child objecting to having her ears excavated with a

washcloth...the baby had reached her limit for the moment.

I returned to splashing Ammu, my three year old charge. She lay

quietly in foot deep water as her trainer and I gave her a good wash.

Every couple of minutes the little "finger" on the end of her wormy

trunk would snake out of the water like the hose of a vacuum cleaner,

and find my hand. The end of an elephant's trunk is so far removed

from the main event that it seems like it's a creature all its own, a

hollow snake with an enormous craw. When her exploring gets out of

hand, her trainer speaks to her in Malayalam, and tells her to keep it

to herself--and she does, doubling it up and submerging it in the

water.

I'm less interested in brillo-ing the dung from Ammu's rump than I am

in revelling in her size, touching her hair and skin--it feels like a

cross between leather and soft rubber. I run my palm along the ends

of her hair: inch long quills that are stiff enough not to tickle, but

soft enough not to hurt.

I have so many questions about the babies, who truly look prehistoric

and not of this world. Unfortunately, none of the trainers speak

English--this evidenced by the response I get when I ask about the

runaway elephant. "Is she mad?" I asked while I pointed to Eva. The

reply was, "No, female."...on second thought, maybe he knew English

perfectly well. After all, any female I know who was ordered to sit

down and be quiet would go running downstream as well.

To my ear, Malayalam words all sound similar...and many people

speaking Malayalam all at once is the equivalent of many radios tuned

to different stations playing in your ear. Not so for the elephants,

who can discern their own trainer's voice from others, and who can

tell the difference between, "Put your legs straight out," and "Pull

your legs together like you're balancing on a ball," or "Head up,

trunk up." At three years old, I doubt I minded as well.

By the time the bathing session was over, we had washed EVERYTHING:

under trunk, under belly, under tail. It's amazing that's animals so

enormous can be trained to behave so well, although, it was a bit

eerie finding a story in the local paper when I returned back to town

detailing the killing of a muhoot (trainer) by an angry elephan

yesterday. Would Ammu ever do such a thing? It didn't seem possible

when I was hugging her head today, reaching across her torso, or

squeezing her trunk. Let's hope not.